Having run my own little voip server at home for a while now, the actual hardware manifestation of this tiny-PBX-thing has varied over the years. Most recently, I had settled on a PXE-booted Raspberry Pi, which was quietly sitting in the corner, bothering nobody.

As with everything in tech, things rot over time. I was quite aware that I was running a pretty old version of Asterisk (version… 11?), and having to keep on top of maintaining a whole other machine / operating system instance just for a PBX seemed a bit inefficient. Given I had a Kubernetes cluster lying around, I wondered: could I replace an entire RPi with a simple k8s deployment (“simple”. Hah!) ?

As it turned out, you can! But there’s a couple of problems to solve.

Static IPv6 Addressing on K8s Pods

How does VOIP The Internet work again?

The connectivity requirements around Voip are interesting and often painful because of the way in which two nodes in a network are expected to communicate. For starters, there are usually multiple protocols involved, with differing requirements. For SIP-based VOIP, you’re using the SIP protocol itself just for connection management and “signalling” - nodes telling each other who they are and what’s happening on the network (calls initiated, hangups etc.). The “media” ( ie the actual voice / video traffic) occurs on a completely different protocol (usually RTP). These problems of “ communicate with another node that I would like to place a call” and “here’s some audio related to an existing ongoing call” have pretty different requirements, hence the use of separate protocols.

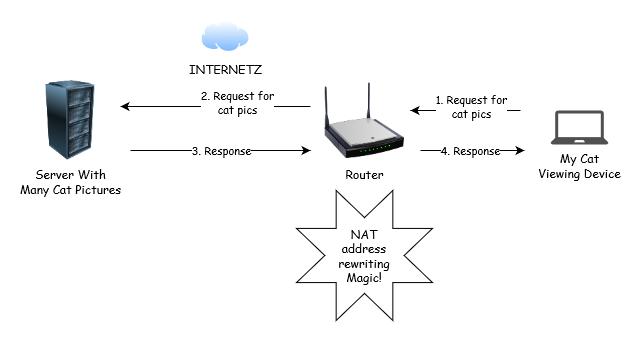

Many typical web protocols (like HTTP, FTP, SSH, DNS) follow a traditional client-server model, where the client connects to the server (usually over TCP, although UDP is sometimes used), and then the server sends any responses generated back down to the client. In other words, network traffic flows exist because of an action taken by the client.

A server under this model would never unilaterally decide to contact a client.

This model works just fine with network features like NAT, where a client might not be routable / reachable from the internet (it’s on private address space). The router that’s implementing NAT can perform “connection tracking”, which is essentially keeping track of packets flowing from the client to an internet-based server (whilst re-writing the source address) so that when the return packet comes back from the server, it can rewrite the destination address to the correct endpoint on the private network.

The router basically has the job of scribbling down every stateful connection that’s being initiated to the internet so that it knows what to do when packets actually come back from the internet.

NAT’s useful for some things, but generally it’s not great. Having the router maintain a giant state table of every connection that’s open between one network and another is expensive and resource-inensive. Also, it’s easy to get the implementation wrong, which is why there are many fun failure modes.

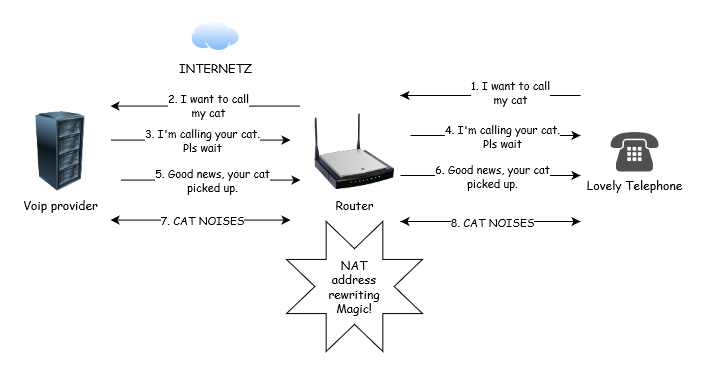

Moreover though, not every protocol or service falls into this model of “CLIENT WANT THING! SERVER GIVE ME THING!”. Specifically, VOIP! The whole point of telephony is that it’s nice to be able to get in touch with people, but also for people to be able to get in touch with me. Sure, if I want to make an outgoing call, the phone / PBX on my local network can contact my internet-based VOIP provider (trunk), and my router can do its ridiculous thing.

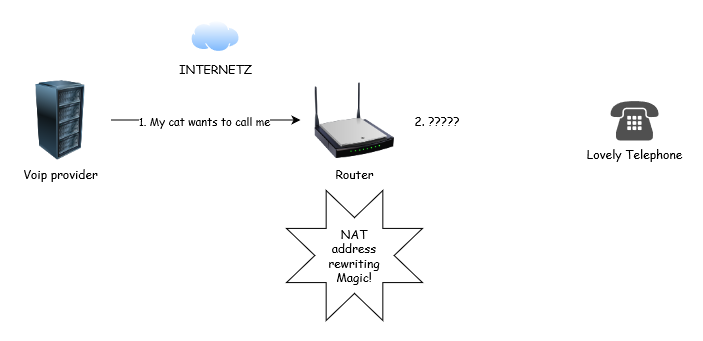

But what if someone wants to phone me? They reach my VOIP provider on the internet, who then sends some SIP packets to my router, which has literally no idea what to do with them (they don’t relate to an existing connection initiated from a client), so drops them on the floor.

There’s a number of solutions to this. Every telephone could maintain an idle TCP connection with the VOIP provider, and then for an incoming call the VOIP provider could just signal over that connection rather than initiating a new one. You could also put fancy static NAT rules on the router so that all incoming connections on a specific port get routed through to a specific device, so no connection tracking. But these all get quite icky quite quickly.

A better idea is to just not use NAT in the first place. If the VOIP client and the VOIP provider can both route directly to each other on unique, globally routable addresses, then they can just initiate connections with each other whenever they like. No-one has to do any rewriting or connection tracking, and life is how it’s meant to be.

NAT is often deployed because IPv4 addresses are scarce and/or there’s two networks that want to talk to each other and their address ranges overlap (which is another way of saying “IPv4 addresses are scarce”). Usefully, humanity invented IPv6 where addresses are not scarce . So let’s use IPv6.

Ok, so we need an IPv6 address on Kubernetes. Easy!

The reason we want Asterisk in the first place is because there’s more than one phone / SIP device behind this router, and I’d like to not need to have to configure each phone to talk to my VOIP provider. Instead, I can configure them to talk to my local Asterisk, and then configure that to route calls up to the internet-based VOIP provider. Similarly, incoming calls can be sent to my Asterisk device which can then use rules to decide what to do with that call (which phone to ring etc.). So, my local Asterisk instance needs to be reachable from the local network and the internet. And I want to run it on Kubernetes.

A standard pattern for deploying containers that need to accept connections from outside the cluster is to configure a service. You can then stand up a Deployment/Daemonset/Whatever and wire that up to your service, and traffic that’s incoming to that service will be routed to a pod that can service that traffic. So in theory, we should be able to deploy Asterisk as a Deployment (with a single Pod), configure a service with an IPv6 address and everything should work.

Well… Yes. Sort of. But there’s one more requirement that makes this interesting. SIP by itself is not an encrypted protocol. Authentication is challenge-based, but only uses MD5 which is now considered obsolete due to cryptographic weaknesses. To mitigate this, my VOIP provider also uses a network access control list (NACL) and therefore only allows specified IPs/networks to connect and authenticate as a given user. The upshot of this, is that in addition to being able to contact my local Asterisk instance on an internet-routable IP, we need to be able to control the outbound traffic and its source address.

The challenge here is that for many Kubernetes / IPv6 deployments, the cluster-cidr configuration parameter (which specifies the networks from which a pod gets its IP address allocated) is set to an RFC4193 “unique local address” subnet (somewhere in fd00::/8) which is analogous to RFC1918 private addressing in IPv4. Essentially, pods get a non-internet-routable IPv6 address. This means that outbound connections to the internet from a pod over IPv6 are…. natted. Oh yes. Often, it’s natted to the IPv6 address of the node that the pod is running on.

Rather than use a service, and do some weird IPv6 nat thing, we can explore the idea of giving a pod an internet-routable IPv6 address, so that traffic gets routed directly to it and outbound traffic has the correct source address. I use Calico as my Kubernetes network provider, and they have a neat mechanism for defining different IP pools and then assigning them to pods.

Let’s say that my home network is on 2001:111:1234:e8b0::/64. For reasons that will become clear, let’s allocate the Asterisk address from a new subnet, 2001:111:1234:e8b1::/64. How about 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1? We can then create a calico IP pool containing just this single address:

apiVersion: crd.projectcalico.org/v1

kind: IPPoolList

items:

- apiVersion: crd.projectcalico.org/v1

kind: IPPool

metadata:

name: asterisk-ipv6-ippool

spec:

natOutgoing: false

blockSize: 128

cidr: 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1/128

ipipMode: Never

nodeSelector: "!all()"

vxlanMode: Never

nodeSelector: "!all()" means “Don’t assign this to any pod on any node automatically”. This IPPoolList can be applied to the cluster with calicoctl apply -f

Now that we’ve got this pool set up on the cluster, we can use an annotation on the Asterisk deployment to hint to the Calico IPAM that the IP address for the pod created for this deployment should have an IP address from this pool:

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: asterisk

labels:

k8s-app: asterisk

spec:

strategy:

type: Recreate

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

k8s-app: asterisk

template:

metadata:

annotations:

cni.projectcalico.org/ipv6pools: "[\"asterisk-ipv6-ippool\"]"

[ ... ]

If we apply our deployment with this cni.projectcalico.org/ipv6pools to the Kubernetes cluster, we can see when we get a shell on the pod that it in fact has an IP address of 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1:

[asterisk]$ ip addr

[...]

3: eth0@if136: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 9000 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

link/ether 82:74:51:25:90:fe brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet6 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1/128 scope global

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

[asterisk]$ curl -6 ifconfig.co

2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1

Wait - how is routing working here?

I’ve skipped over a bit. I never changed any configuration on the router, so how does the router know where to send packets for 2001:111:1234:e8b1::/64? There’s no interface on the router configured with 2001:111:1234:e8b1::/64. It’s got 2001:111:1234:e8b0::/64 on its local LAN interface, so it knows how to get to the Kubernetes nodes (and other hosts), but it should in theory be routing 2001:111:1234:e8b1::/64 back out to the internet (the default route). So how is this working?

In short, BGP. BGP to the rescue.

Ages ago, I configured Kubernetes to BGP peer with my router using MetalLB. For… reasons, I ended up replacing MetalLB with Calico’s own BGP configuration. This has the upshot that my router knows about any Calico IP Pools that exist and knows how to route traffic bound for those IPs to the right host.

Creating the Calico IP pool itself doesn’t have any effect, but the moment I applied the Asterisk deployment with the Calico annotation to choose an IP address from the specific IP pool, BGP magic happens and the route pops up in the router.

[router]$ gobgp global rib -a ipv6

Network Next Hop AS_PATH Age Attrs

*> 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1/128 2001:111:1234:e8b0::14 00:00:01 [{Origin: i} {Med: 0} {LocalPref: 100}]

[...]

So any packets arriving for 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1, the router will forward to 2001:111:1234:e8b0::14, which is the Kubernetes node that’s running the pod. Calico then knows how to take that traffic and forward it to the right pod.

Why not just use an address in the existing subnet?

This seems like a bit of faff. If we’ve already got an IPv6 subnet, why not just assign Asterisk an address from there?

Ultimately, this is because of IPv6’s Neighbor Discovery Protocol, which is a little bit like ARP in IPv4’s world. ND is the mechanism through which IPv6 hosts on the same subnet find each other. Two hosts on the same subnet should be able to route directly to each other without going via a router, and ND provides a mechanism for that to happen.

But, IPv6 ND is a little complex, and there’s lots of fun mucking around in ICMP needed to get IPv6 ND to work properly. The Asterisk pod that has our IPv6 endpoint address is not going to be able to send arbitrary ICMP packets to the network its host node is connected to. It doesn’t have privileges for that, and from Calico’s perspective it’s not even on the same network segment as the node’s network.

There’s probably a way you could make it work, but a separate subnet makes more sense.

Oh no, I have a phone that doesn’t support IPv6

Alas, my doorbell is a SIP device which doesn’t support IPv6. It has no way of talking to my Asterisk instance. Unless… we give the Asterisk instance an IPv4 address as well! Let’s pick a subnet we’re not using, say 10.10.10.0/24 and pick an address: 10.10.10.2.

Create the Calico IP pool:

apiVersion: crd.projectcalico.org/v1

kind: IPPoolList

items:

- apiVersion: crd.projectcalico.org/v1

kind: IPPool

metadata:

name: asterisk-ipv4-ippool

spec:

natOutgoing: false

blockSize: 32

cidr: 10.10.10.2/32

ipipMode: Never

nodeSelector: "!all()"

vxlanMode: Never

Add the annotation cni.projectcalico.org/ipv4pools: "[\"asterisk-ipv4-ippool\"]" to the deployment:

[asterisk]$ # ip addr

[...]

3: eth0@if228: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 9000 qdisc noqueue state UP group default

link/ether 1e:1e:0a:05:e4:0f brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 10.10.10.2/32 brd 10.10.10.2 scope global eth0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 2001:111:1234:e8b1::1:1/128 scope global

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

and check the routing table on the router:

[router]$ gobgp global rib -a ipv4

Network Next Hop AS_PATH Age Attrs

*> 10.10.10.2/32 192.168.2.20 00:12:30 [{Origin: i} {Med: 0} {LocalPref: 100}]

Now the doorbell can contact Asterisk on 10.10.10.2. This is fine, because we’re not trying to get asterisk to contact anything on IPv4, so there’s no weird NAT issues to deal with. Doorbell contacts Asterisk on IPv4, and if Asterisk needs to do anything upstream it does that over lovely globally routable IPv6.

In part 2, I’ll talk a bit about how to actually configure Asterisk to do all of this properly and how that configuration can be managed on Kubernetes.