I’ve been running my own build router at home for a while now. Having previously run OpenWRT, pfSense and a few others, I decided a while back that running a linux box would provide some pretty effective capabilities (ppp, VLANs etc) while also having a proper grown up OS and package ecosystem to play with. This is how I ended up with a small x86 box running Debian 8 as my home router.

Some time after that, I came across ntopng which seemed to effectively answer the question of “What flows are going where?”.

However, after a while, it became apparent that while the functionality was good, the stability was less so. This led me down a path to try and find something better. This thing is basically a combination of using an iptables module to output netflow/ipfix flows to Logstash, which can then pipe them into Elasticsearch.

IPTables

IPTables is both awesome, and extensible. Which means you can just write a kernal module and get it to do whatever you like! Usefully, someone has written an iptables module that can output netflow & IPFIX traffic. For this, I used IPFIX - Netflow is the original protocol invented by Cisco, and IPFIX is the evolved and more standardised IETF version.

The installation instructions in the github repository are pretty comprehensive. Once the module is built and compiles, I added the ipt_NETFLOW line into /etc/modules (I’m on Debian 8, other distributions may vary) to ensure it gets loaded at boot time. To configure the module, I created /etc/modprobe.d/ipt_NETFLOW.conf with the following:

options ipt_NETFLOW destination=127.0.0.1:2055 protocol=10 natevents=1

This configures IPFIX (protocol=10) and to output the flows to a listener on localhost, port 2055. The flow traffic is UDP, so you could in theory put this on a remote host if you were so inclined.

To load the module immediately, you can simply:

$ modprobe ipt_NETFLOW destination=127.0.0.1:2055 protocol=10 natevents=1

Now that the module is loaded, we have an iptables target called NETFLOW we can use to send traffic to. In my case, I wanted to log all traffic that had been explicitly allowed by iptables. A typical iptables setup might have (for example) the INPUT chain have a policy of DROP and then a few rules to accept some traffic. The ipt_NETFLOW documentation talks about adding a rule at the top of each chain to generate a netflow regardless of whether that traffic is going to be dropped or accepted. In my case, I only really cared about accepted traffic so I created a new chain called ACCEPTANDACCOUNT with the following rules:

-A ACCEPTANDACCOUNT -j NETFLOW

-A ACCEPTANDACCOUNT -j ACCEPT

This means that in my rules I can simply send traffic I want to allow to ACCEPTANDACCOUNT as opposed to ACCEPT, and it will generate a flow and then accept the traffic. This also lets me exclude some flows from netflow, e.g. traffic on localhost.

One of the advantages of using IPFIX is that it fully supports IPv6, so you can use the same target on ip6tables as well.

Logstash

Now that we’ve got iptables merrily chucking UDP flows to a local socket, we need to actually listen and process these before sending them off to elasticsearch. Thankfully, Logstash can do exactly that. I’m using version 5.

Logstash comes with an input filter that can be used to capture netflow traffic:

input {

udp {

type => "netflow"

port => 2055

codec => netflow {

netflow_definitions => "/usr/share/logstash/vendor/bundle/jruby/1.9/gems/logstash-codec-netflow-3.1.2/lib/logstash/codecs/netflow/ipfix.yaml"

versions => [10]

}

}

}

The value of netflow_definitions should point to the local installed copy of ipfix.yaml which should be wherever the logstash-codec-netflow gem is installed.

Once we’re capturing the netflow traffic as events, it’s useful to do some processing to the events:

Map IP protocol identifier

IPFIX carries the IP protocol as a numeric value. No-one ever remembers what these are, so it’s useful to map known values to a string:

translate {

field => "[netflow][protocolIdentifier]"

destination => "[netflow][protocolIdentifierString]"

override => "true"

dictionary => [ "6", "TCP", "17", "UDP", "1", "ICMP", "47", "GRE", "50", "ESP", "58", "IPv6-ICMP" ]

}

This will preserve the value in the protocolIdentifier field, but if possible create a new protocolIdentifierString field containing the mapped value.

Reverse DNS lookups

Logstash can do a reverse DNS lookup for us on the source / destination IP addresses. To achieve this, we need to first copy the values of sourceIPv4Address and destinationIPv4Address to new fields to contain the name. This is so that if the reverse DNS fails, the field that should contain the name still contains the address.

mutate {

add_field => ["sourceName", "%{[netflow][sourceIPv4Address]}"]

add_field => ["destName", "%{[netflow][destinationIPv4Address]}"]

}

Then, we can simply ask logstash to do a reverse lookup:

dns {

reverse => ["sourceName","destName"]

action => "replace"

}

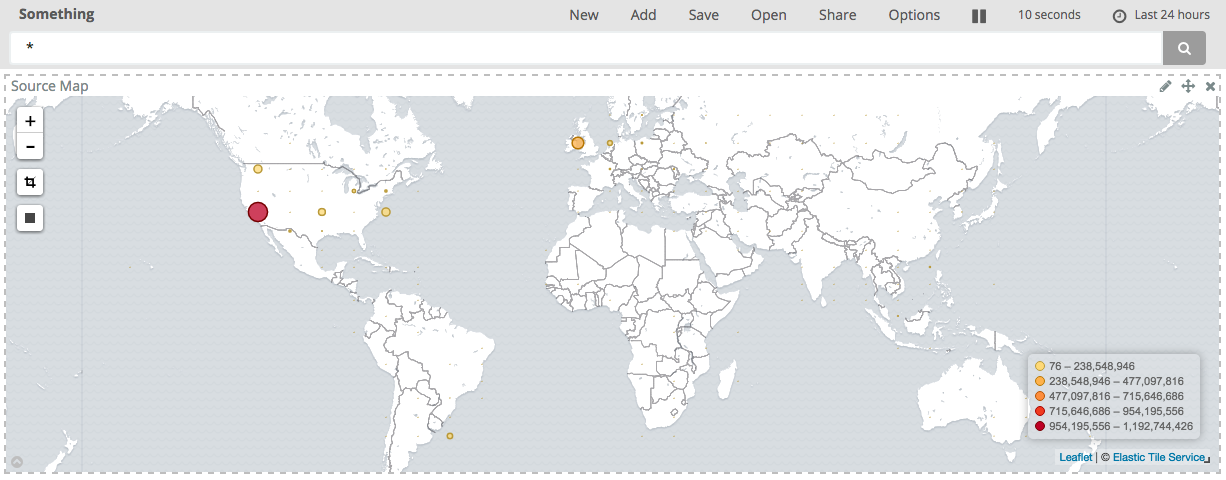

GeoIP

A very cool thing that Logstash can do is take an IP address and use the Maxmind GeoIP2 databases to map that to a physical location. To do this, we first need to get a copy of the database. The full resolution version is commercially licensed, but there is a ‘lite’ version that is free to use. On Debian, this is a little challenging as the default package geoip-database-contrib only grabs the legacy versions which Logstash deprecated in the latest version. Therefore, to get the latest version, a different approach is needed.

Usefully, Maxmind maintain an Ubuntu PPA (ppa:maxmind/ppa) containing a deb package for an updated downloader. Also usefully, it’s possible for debian to pull down the sources from a PPA and build a vanilla-Debian package. From https://wiki.debian.org/CreatePackageFromPPA:

$ apt install devscripts build-essential

$ echo "deb-src http://ppa.launchpad.net/maxmind/ppa/ubuntu wily main" > /etc/apt/sources.list.d/maxmind-ppa.list

$ apt-key adv --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --recv-keys DE742AFA

$ apt update

$ apt-get source --build geoipupdate

$ dpkg -i geoipupdate_*.deb

Once done, you should find a binary at /usr/bin/geoipupdate. I only want the non-commercial databases so updated the configuration file at /etc/GeoIP.conf to read:

UserId 999999

LicenseKey 000000000000

ProductIds GeoLite2-City GeoLite2-Country GeoLite-Legacy-IPv6-City GeoLite-Legacy-IPv6-Country 506 517 533

Once done, running geoipupdate will download the relevent databases and put them in /usr/share/GeoIP. This allows us to configure the last Logstash filter:

geoip {

database => "/usr/share/GeoIP/GeoLite2-City.mmdb"

source => "[netflow][sourceIPv4Address]"

target => "geoip_src"

}

geoip {

database => "/usr/share/GeoIP/GeoLite2-City.mmdb"

source => "[netflow][destinationIPv4Address]"

target => "geoip_dest"

}

This will do a lookup of the source / destination IPv4 addresses and add them to new fields called geoip_src and geoip_dest.

IPv4 / IPv6

One small point is that IPFIX supports both IPv4 and IPv6 flows. Logstash can do reverse DNS and geoip lookups on both, so we can apply these lookups to either the source/dest IPv4 depending on which one is present. For example:

if ("" in [netflow][sourceIPv4Address]) {

<geoip / mutate the source / dest IPv4 fields>

} else if ("" in [netflow][sourceIPv6Address]) {

<geoip / mutate the source / dest IPv6 fields>

}

Output

Finally, we output records to Elasticsearch:

if [type] == "netflow" {

elasticsearch {

index => "logstash_netflow-%{+YYYY.MM.dd}"

hosts => ["elasticsearch.example.com"]

manage_template => false

}

}

We want to manage the ES template ourselves which gives us a bit greater flexibility over field types.

Elasticsearch & Kibana

The final part of this is to configure Elasticsearch to index the fields correctly. If you set the previous up and just pointed it at an ES cluster, data would happily flow into it. However, ES would take a guess at the formats of some of the fields and not necessarily always get it right. Therefore, it’s useful to give it a template of what types to index different fields as, especially as we know in advance.

Specifically, it’s useful to make sure that the IP address fields are set to type ip - Elasticsearch 5 now supports both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses in this type; and for the geoip_src.location / geoip_dest.location fields are type location.

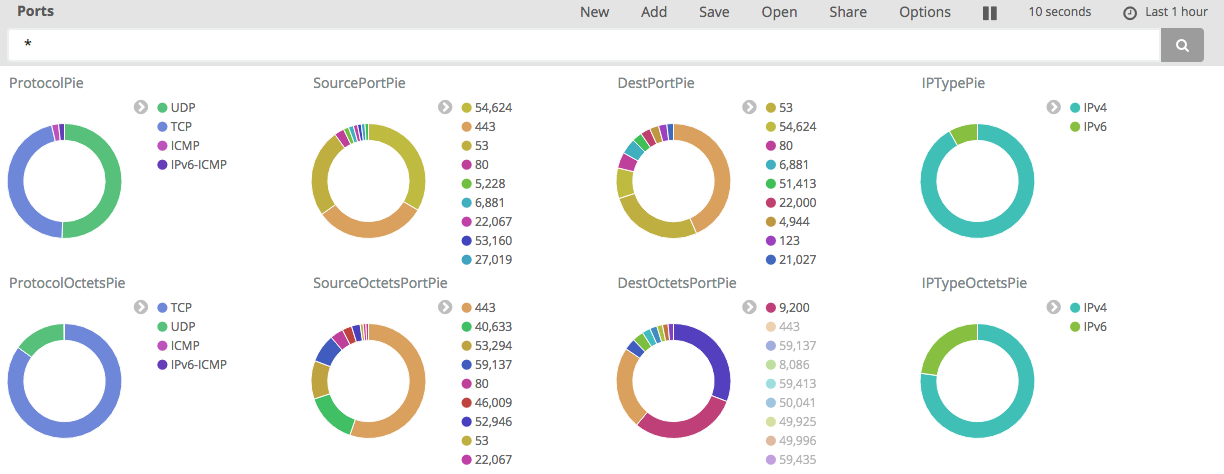

Putting it all together with Kibana, you can start to pull together some pretty pictures: